by Laurence | May 31, 2008 | Social search

So Rob Curley has left the Washington Post, where he was a high-profile architect of the Post’s vision for “hyperlocal” — a buzzy label for Web products that promise to keep you in touch with your local community.

Curley’s main creation at the Post was LoudounExtra.com, a Web site devoted to Loudoun County, VA, which happens to be Loladex’s home base. Still in the wings is a similar site for our neighboring county of Fairfax.

Local guru Peter Krasilovsky did a good Curley summation here and a follow-up interview here; I won’t rehash the details. Instead, I’ll just say that I hope the Post takes this opportunity to retool its approach to hyperlocal.

Why? After all, doesn’t my hometown newspaper deserve praise for even facing the challenge of hyperlocal? Among its peers, the Post has been by far the most serious about rethinking its local coverage, right?

Yes, true enough. But by now it’s clear that Curley’s vision wasn’t terribly fruitful. The Loudoun site is looking somewhat neglected, for one thing, and I hear that usage isn’t great. The key problem, however, remains one of conception.

The issue, in short: Curley elected to build the Post’s hyperlocal strategy around … a countywide site?

Fact is, LoudounExtra.com is no more local than the twice-weekly printed section that the Post was already devoting to Loudoun. Calling the Web site “hyperlocal” makes sense only for someone looking down from 30,000 feet.

OK, so the Web site has some extra headcount and is updated several times daily. It can cover more stuff than the print version. It also supplements its coverage by pointing at other news sources.

And it has built a few specialized databases: Restaurants, churches, schools.

But none of this is new or especially Web-oriented. If the Post had given its print staff a bundle of money and permission to publish the Loudoun section daily, I suspect we’d be looking at much the same thing.

Curley tells Peter K. that the new Fairfax site will be more granular — since Fairfax has a population of 1 million, four times as big as Loudoun’s, I’d hope so — and will be accessible via town-specific URLs that presumably will produce different-looking home pages.

I guess we’ll see, but I doubt it’ll feel truly local. If it were really a town-specific approach, why would they call it Fairfax Extra?

So what is hyperlocal, if not the Curley vision?

Here’s my own definition: It’s the things we wonder about as we walk (or drive) the streets of our community. Today, for instance, I was thinking —

• What’s with that used-book store? The sign in its window seems to say its business is failing.

• What’s the asking price for that house? What does it look like inside? Why are they selling, anyway?

• Have any of my friends been to that new restaurant? Could I take the kids?

You were thinking completely different things, I’m sure. And that’s the point: Hyperlocal should be relevant to you. It should be about your day-to-day concerns in your local community. Those definitions are personal, so hyperlocal must be personal, too. And LoudounExtra.com just ain’t.

Even though I live in Loudoun County, for instance, I don’t care about a house fire in Sterling. Even though I live in Leesburg, I don’t care that the Raiders made it to the state softball tournament. Stories like these fall outside my personal radius of interest — geo interest, or subject interest, or both.

A plain old local site might not understand this. It might be the same for everyone, like a newspaper. But a hyperlocal site should understand personal radii. If I must wade through irrelevant content when I enter, it’s not hyperlocal enough.

What’s more, house fires and softball tourneys are the same old newspaper fare. Even the Post’s designated local bloggers mostly do newspaper-style reporting, albeit with an occasional “I” or “me” thrown in.

If it wants to become more relevant locally, the Post must move toward a model that’s more social … more conversational … more authentic … less mediated. It must give us what newspapers usually don’t: The voices of our neighbors and friends.

To do this, a site must leverage its community. It must facilitate conversations.

No one knows the exact right mix of editorial and community, of course. And there are other ingredients that add complexity, such as data and feeds and photos. It’s not easy.

Still, I can recognize the wrong mix. I recall being taken aback last year when Curley was quoted in a New York Times story about the launch of LoudounExtra.com:

“Most hyperlocal sites are 100 percent community publishing sites,” Mr. Curley said. “This is 1 percent community publishing.”

OK, so 100 percent community isn’t right. No argument there. But 1 percent is far, far worse.

Now if only Curley had said LoudounExtra.com is “38 percent community publishing,” I might have called him a genius.

There are plenty of hyperlocal models out there besides the Post. In fairness, none has nailed this formula. Many national efforts work by aggregating other news outlets and blogs, sometimes with a paid human thrown in for flavor: Outside.in and Topix and Marchex’s new just-killed [see comments] MyZip Network come to mind. None of them work quite right.

A site that’s far closer to capturing the hyperlocal spirit, I think, is Brownstoner in Brooklyn, NY. It’s mostly a blog, and it’s run by Jonathan Butler, a former colleague from my magazine days.

Brownstoner isn’t exactly hyperlocal, because it covers all of Brooklyn. But the site works because it speaks to an audience that shares a state of mind — urban homesteaders, I guess you’d call them — and somehow makes the huge borough seem like a single neighborhood.

It’s missing some local staples (sports, for instance), but with its mix of bloggers and attitude, plus its clever focus on real estate, it artfully captures the essence of living in, say, Cobble Hill.

This inspires tremendous engagement among its users: Brownstoner’s very frequent blog posts often draw many dozens of comments within hours. By contrast, today’s top two most-commented stories on LoudounExtra.com (which admittedly covers far less territory) had 6 comments between them.

So, my thought for the day:

Take a curated blog approach, where selected amateurs and semi-pros post frequently (like Brownstoner). Combine it with the news stream of a social network and utilities such as (ahem) Loladex. Add smart feeds for real estate listings and crime and government and other media and other blogs.

Give users the tools to participate in every conversation, and make it clear that their participation is central to the site.

Allow users to specify what they care about. Enable them to enjoy their personalized mix via the Web site, or their RSS reader, or their e-mail, or their phone.

Finally, deliver this all with a minimum of filigree — just a stream of highly relevant items in the manner of Facebook’s News Feed.

That would be hyperlocal, I think. The pulse of your community.

I wish the Post would do something like this, because I’d use it. Meanwhile, I haven’t used LoudounExtra.com for months. And I suspect I’m not alone.

by Laurence | May 25, 2008 | Local search, Loladex

Via Andrew Shotland, I recently saw this post. I know I’ll be called naive, but I was surprised at its blatancy.

This guy Stephen Espinosa (whom I don’t know) helps local businesses promote themselves online. His advice is to get your “clients” to post reviews on popular sites — the quote marks are his, and he adds a smiley face in case we don’t get it:

I won’t spell it out fully, since he doesn’t, but this seems like an opportune moment to talk about fake reviews.

You need spend only a few minutes on most rate-and-review sites to understand that they contain fake reviews. There are fake positive reviews posted by the business owners, and fake negative reviews posted by their competitors. Many are amateurish and easy to identify if you’re looking for them, though I suspect that some casual users don’t realize they’re fake.

I’ve never put much store in reviews by strangers. Still, I always thought that out-and-out fakes were a fairly limited and unorganized phenomenon. Now that I see they might be promoted more systematically, I’ve lost confidence that I can even spot a fake.

Furthermore, I expect that such fakery will spread and become more sophisticated. As local search reaches critical mass, it’ll be hard to trust anything.

I used to believe, for instance, that a Yelp reviewer with 10+ reviews and some kudos from friends was almost certainly a real person. That’s probably still a safe assumption — but will it be next year?

If I’m a certain type of SEO consultant, right now I’m probably setting up a network of hundreds of fake Yelpers. They’ll all have real-looking pictures, real-sounding profiles, and lots of reviews (some even genuine). They’ll send each other kudos, enhancing each others’ credibility.

And they’ll exist solely so I can be paid to deploy them for the benefit of my clients.

If done properly, this sort of fakery will be very hard to detect. Probably the only way I’d get caught would be to advertise the service — or to include quote marks and smiley faces when I blogged about it.

And this is just the truly fake reviews. There’s still reviews from friends of the business owner, and “real” reviews that have been solicited directly by business owners, some of whom will give discounts in exchange for posting on … well, on a certain site.

In such a world, reviews by strangers become devalued and personal trust is at a premium.

Not so long ago I heard that we need to see, on average, 20 reviews from strangers before we’ll believe the prevalent opinion that’s being expressed.

What will that number be in the future? 50? 100?

Wouldn’t it be simpler and better to get your advice from people you know and trust?

Via, say, Loladex?

by Laurence | May 25, 2008 | Loladex, Social search

My previous post was about why you’d want to use Loladex. This post is about the nitty-gritty of getting people to do so.

Fair warning: If you don’t care about the inner workings of Facebook, this may not fascinate you.

OK, so we have this Loladex product. Among other things, it allows you to ask your friends for advice on local businesses. You might need help finding a good electrician, for instance.

Because Loladex delivers advice from your friends, it works best when it’s hooked into a social network. And among the social networks, we like Facebook best: It’s unmatched in its combination of audience size, integration tools, and viral channels.

So we launched Loladex on Facebook.

And two months later we still like Facebook. But …

But even on Facebook, our users can’t be fully social. And therefore they can’t get the full benefit of Loladex. It’s harder than I’d like, for example, to ask my friends if they know … well, a good electrician.

This isn’t just a problem for us. It’s Facebook’s problem, too, because real-life applications like Loladex are what Facebook needs in order to build long-term relevance.

So far our biggest issues have been:

- Facebook’s lack of clarity about how its own systems work; and

- The poisoned atmosphere that’s been created by many Facebook applications.

First, lack of clarity about Facebook’s internal workings.

For sure, this is partly our own fault. We’re still climbing the Facebook learning curve. Sometimes we just don’t know where to look for information.

Also, Facebook is a young company, moving quickly and constantly changing its own rules. It’s just about to launch a big redesign, for example, and we don’t really know how it’ll affect us. We accept that.

But Facebook makes things worse by being deliberately mysterious about some of its key features. A classic example is the News Feed that appears on everyone’s Facebook home page.

If you’re a Facebook user, you’re familiar with the News Feed: It shows you what your friends have been doing and saying on Facebook, and sometimes on other sites too. In an ideal world, Loladex could use it as a reliable communication channel.

The thing is, your News Feed shows only a small slice of your friends’ activity. Facebook decides which items will (and won’t) be displayed. It does so the same way Google assembles its search-results pages — via an algorithm that it changes often and will describe only vaguely.

There’s a reason for this, of course. Like the Google search-results page, the News Feed is valuable real estate. Publish an exact formula and it’ll be abused by spammers and others.

Still, the secrecy means we must work within an uncertain system. We follow Facebook’s guidelines, but often it doesn’t help. So we dive into the many long, geeky Facebook discussions that have flowered across the Web. Some tips are helpful, others are either outdated or wrong.

Sorting through all this vague and unreliable information is a time drain for Loladex. Experimenting with different methods, even more so. But both are necessary, unfortunately.

To complicate mattters, it’s tough to know when we’ve solved a problem. Unlike Google, where everyone sees the same search-results page (more or less), everyone’s News Feed is different. Even when something seems to work, it may not be working for everyone.

OK, now for our second big issue: The bad faith of many Facebook applications.

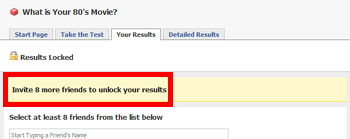

Simply put, Facebook’s utility is being crippled by all the dumb, spammy and downright abusive applications it enables. See below for a typical example of how such applications spread:

These black hats make it difficult for Loladex to build a white-hat application, for at least two big reasons:

- Rather than making communication easier among its users, Facebook has been making it harder. It has tried to devise formulas that’ll penalize only “bad” applications, but everyone gets snagged to some degree.

- Because of the ongoing torrent of crap, some Facebook users have stopped clicking any buttons that might send a message to their friends. Many also ignore every single invitation they get. Or if they add an app, they disable the very communication features that’ll make it work properly.

The net effect is a big damper on Facebook’s potential, and a tougher task for Loladex.

I remain a fan of Facebook, but I’m not sure it understands the depth of its problem here. I’m reminded of when AOL was reviled for assaulting its users with pop-up ads. Eventually management shut them down, but it took too long and there were too many half-measures along the way. AOL was definitely hurt; arguably, it never recovered.

So what’s to be done? How do we overcome these issues so that Loladex users can get the most from Facebook?

In the short run, we’re working on our own solutions. I’ll blog about them as we roll them out in the coming weeks.

In the medium run, though, I believe Facebook must make some changes.

Specifically, Facebook must start discriminating between applications — and not just via its algorithms, a tactic that ultimately punishes its users. Besides policing bad apps, Facebook should be using human beings to identify and favor applications that can be useful in people’s regular lives, because their growth is in the company’s strategic interest.

Exactly how to favor such apps is up to Facebook. I would suggest easier access to the News Feed and a more prominent “request” mechanism, achieved via clear procedures that don’t need to be secret because they’re open only to approved applications.

Whatever the method, it’d be refreshing to see Facebook focus once again on making communication easier — not on shutting it down.

In this vein, there have been rumblings lately, apparently false, that the company might add a “preferred developer” or “preferred application” program. I would welcome such a program, and I’d happily pay to participate.

If I were Facebook, I’d make it work something like this:

• Applications must fall into categories that are judged to be strategic to Facebook. The list of categories could start small & be expanded.

• Applications must have existed for X weeks, and during that period must have met minimum standards for non-spamminess.

• Applications must follow all of Facebook’s rules and recommended practices. (Facebook should be documenting more of these rules and practices.)

• As a token of their seriousness, developers pay an upfront fee to participate. In return, Facebook gives them an equivalent advertising credit.

• Developers include a prominent, standardized way for users to complain to Facebook, which hires user advocates to field these complaints. The process should be human: If developers don’t work in good faith to fix problems, the advocates may yank their privileges.

• Approved applications are clearly identified as “safe” by Facebook to its users.

The exact mechanics don’t matter, however. The main thing is, this requires human intervention. Facebook can’t rely on statistics alone to recognize and promote the applications that will turn it into a fully functioning community.

Which categories and applications should be promoted? Again, that’s up to Facebook. I don’t know what they’re aiming for, but I’m pretty sure they can’t be thrilled with the current mix, or the resulting assessments of their platform.

In any rational process, I’m confident that applications such as Loladex will be part of the solution. As such, they should get more help than, say, Vibrating Hamster — which may be a part of the solution itself, I suppose, but for an entirely different problem.

by Laurence | May 21, 2008 | Competitors, Local search, Loladex, Social search

Why would anyone start using Loladex? We get asked this question a lot.

I’ve posted before about the chicken-and-egg issue, albeit in general terms. Probably I should update those thoughts: Since we started focusing on social networks, we’ve learned a bunch.

But for now, let me address Loladex’s specific challenge: How do we motivate people to rate local businesses via a Facebook application? Why would anyone do such a thing?

Well, for many reasons, of course. One day I’ll list them all. But I’d like to highlight one reason in particular, partly because I think it’s powerful and partly because it illustrates a big difference between Loladex and two of its biggest competitors — Yelp and Angie’s List.

Here it is: Loladex believes people will rate local businesses to help their friends.

By friends, I mostly mean actual, real-world friends. People you might have dinner with. For most folks, that’s a subset of “Facebook friends.”

Let’s get specific. Why would anyone use Loladex to rate, let’s say, a plumber? Or a pediatric gastroenterologist? Certainly it’s not something you do on a whim. Loladex won’t be running ads that say “Rate pediatric gastroenterologists!” — and if we did, we wouldn’t expect many clicks.

But suppose you were asked directly by a friend whose kid needed a medical specialist? If you knew of a good gastroenterologist, would you take a minute to make the recommendation? If you were seeking such a specialist, would you value this sort of recommendation?

We think so. Such recommendations are an everyday part of friendship, and numerous surveys tag them as a more powerful force than the Yellow Pages, a $14 billion industry.

With Loladex, we want to provide a channel for these person-to-person recommendations.

Contrast this to Yelp. I always say I like Yelp — and I do — but Yelp isn’t about helping your real-world friends. By and large, the people who rate businesses on Yelp do it for reasons of (a) self-expression; and (b) social standing in an online community that may overlap with their real-world friends, but doesn’t have to.

These mostly twentysomething Yelpers provide a service for us all, God love them. But it’s almost never a person-to-person transaction. Also, the motivation to rate something on Yelp fades quickly outside its core realm of restaurants & other social venues.

Or consider Angie’s List. I’m not a fan of Angie’s List, simply because it’s a subscription service. If it were free, I’d love it. They’ve built something that’s clearly valuable to their users — and they’ve focused their brand admirably, defining it around home services.

Again, though, Angie’s List isn’t about helping your real-world friends. It’s mostly a community of cooperating strangers who share ratings because they understand the value of the site’s virtuous circle. There’s an implicit quid pro quo.

Both Yelp and Angie’s List have powerful models. Loladex aims to tap many of the same motivations; we’d be silly not to. But mainly we’re about recommendations from your friends. We’re trying to bring this everyday personal interaction into your online world.

OK, so much for the theory. How’s the “help a friend” strategy working for us, specifically on Facebook?

To be honest, it’s a learning experience.

More in Part 2.