by Laurence | May 31, 2008 | Social search

So Rob Curley has left the Washington Post, where he was a high-profile architect of the Post’s vision for “hyperlocal” — a buzzy label for Web products that promise to keep you in touch with your local community.

Curley’s main creation at the Post was LoudounExtra.com, a Web site devoted to Loudoun County, VA, which happens to be Loladex’s home base. Still in the wings is a similar site for our neighboring county of Fairfax.

Local guru Peter Krasilovsky did a good Curley summation here and a follow-up interview here; I won’t rehash the details. Instead, I’ll just say that I hope the Post takes this opportunity to retool its approach to hyperlocal.

Why? After all, doesn’t my hometown newspaper deserve praise for even facing the challenge of hyperlocal? Among its peers, the Post has been by far the most serious about rethinking its local coverage, right?

Yes, true enough. But by now it’s clear that Curley’s vision wasn’t terribly fruitful. The Loudoun site is looking somewhat neglected, for one thing, and I hear that usage isn’t great. The key problem, however, remains one of conception.

The issue, in short: Curley elected to build the Post’s hyperlocal strategy around … a countywide site?

Fact is, LoudounExtra.com is no more local than the twice-weekly printed section that the Post was already devoting to Loudoun. Calling the Web site “hyperlocal” makes sense only for someone looking down from 30,000 feet.

OK, so the Web site has some extra headcount and is updated several times daily. It can cover more stuff than the print version. It also supplements its coverage by pointing at other news sources.

And it has built a few specialized databases: Restaurants, churches, schools.

But none of this is new or especially Web-oriented. If the Post had given its print staff a bundle of money and permission to publish the Loudoun section daily, I suspect we’d be looking at much the same thing.

Curley tells Peter K. that the new Fairfax site will be more granular — since Fairfax has a population of 1 million, four times as big as Loudoun’s, I’d hope so — and will be accessible via town-specific URLs that presumably will produce different-looking home pages.

I guess we’ll see, but I doubt it’ll feel truly local. If it were really a town-specific approach, why would they call it Fairfax Extra?

So what is hyperlocal, if not the Curley vision?

Here’s my own definition: It’s the things we wonder about as we walk (or drive) the streets of our community. Today, for instance, I was thinking —

• What’s with that used-book store? The sign in its window seems to say its business is failing.

• What’s the asking price for that house? What does it look like inside? Why are they selling, anyway?

• Have any of my friends been to that new restaurant? Could I take the kids?

You were thinking completely different things, I’m sure. And that’s the point: Hyperlocal should be relevant to you. It should be about your day-to-day concerns in your local community. Those definitions are personal, so hyperlocal must be personal, too. And LoudounExtra.com just ain’t.

Even though I live in Loudoun County, for instance, I don’t care about a house fire in Sterling. Even though I live in Leesburg, I don’t care that the Raiders made it to the state softball tournament. Stories like these fall outside my personal radius of interest — geo interest, or subject interest, or both.

A plain old local site might not understand this. It might be the same for everyone, like a newspaper. But a hyperlocal site should understand personal radii. If I must wade through irrelevant content when I enter, it’s not hyperlocal enough.

What’s more, house fires and softball tourneys are the same old newspaper fare. Even the Post’s designated local bloggers mostly do newspaper-style reporting, albeit with an occasional “I” or “me” thrown in.

If it wants to become more relevant locally, the Post must move toward a model that’s more social … more conversational … more authentic … less mediated. It must give us what newspapers usually don’t: The voices of our neighbors and friends.

To do this, a site must leverage its community. It must facilitate conversations.

No one knows the exact right mix of editorial and community, of course. And there are other ingredients that add complexity, such as data and feeds and photos. It’s not easy.

Still, I can recognize the wrong mix. I recall being taken aback last year when Curley was quoted in a New York Times story about the launch of LoudounExtra.com:

“Most hyperlocal sites are 100 percent community publishing sites,” Mr. Curley said. “This is 1 percent community publishing.”

OK, so 100 percent community isn’t right. No argument there. But 1 percent is far, far worse.

Now if only Curley had said LoudounExtra.com is “38 percent community publishing,” I might have called him a genius.

There are plenty of hyperlocal models out there besides the Post. In fairness, none has nailed this formula. Many national efforts work by aggregating other news outlets and blogs, sometimes with a paid human thrown in for flavor: Outside.in and Topix and Marchex’s new just-killed [see comments] MyZip Network come to mind. None of them work quite right.

A site that’s far closer to capturing the hyperlocal spirit, I think, is Brownstoner in Brooklyn, NY. It’s mostly a blog, and it’s run by Jonathan Butler, a former colleague from my magazine days.

Brownstoner isn’t exactly hyperlocal, because it covers all of Brooklyn. But the site works because it speaks to an audience that shares a state of mind — urban homesteaders, I guess you’d call them — and somehow makes the huge borough seem like a single neighborhood.

It’s missing some local staples (sports, for instance), but with its mix of bloggers and attitude, plus its clever focus on real estate, it artfully captures the essence of living in, say, Cobble Hill.

This inspires tremendous engagement among its users: Brownstoner’s very frequent blog posts often draw many dozens of comments within hours. By contrast, today’s top two most-commented stories on LoudounExtra.com (which admittedly covers far less territory) had 6 comments between them.

So, my thought for the day:

Take a curated blog approach, where selected amateurs and semi-pros post frequently (like Brownstoner). Combine it with the news stream of a social network and utilities such as (ahem) Loladex. Add smart feeds for real estate listings and crime and government and other media and other blogs.

Give users the tools to participate in every conversation, and make it clear that their participation is central to the site.

Allow users to specify what they care about. Enable them to enjoy their personalized mix via the Web site, or their RSS reader, or their e-mail, or their phone.

Finally, deliver this all with a minimum of filigree — just a stream of highly relevant items in the manner of Facebook’s News Feed.

That would be hyperlocal, I think. The pulse of your community.

I wish the Post would do something like this, because I’d use it. Meanwhile, I haven’t used LoudounExtra.com for months. And I suspect I’m not alone.

by Laurence | Mar 10, 2008 | Local search

From Canada’s Financial Post, here’s an interesting summing-up of last year’s Geosign implosion, courtesy of Ahmed Farooq of iBegin.

(Alas, I had skipped over an earlier post on this topic from Peter Krasilovsky, so this was mostly news to me.)

The short version: Geosign operated a bunch of domains that existed solely to serve ads. Some of these sites included ‘real’ content as a cynical fig leaf.

Googlers know how it goes: You search for ‘XYZ’ and click on an ad (or a result) that looks promising, only to land on a site full of more XYZ-related ads — some of which lead to yet more ad sites, the AdSense version of an infinite loop.

Since advertisers pay by the click, this provides easy money for companies that are willing to waste your time. ‘Arbitrage’ is the common — rather charitable — name for the method.

Google ultimately cut off Geosign, presumably because it was hurting the value of Google’s ads, and the company fell apart.

As a strategy, arbitrage isn’t so dissimilar from search-engine marketing (SEM), or even from search-engine optimization (SEO); it’s all a matter of degree. And when your content is advertising, as it is for Yellow Pages sites, the line gets even blurrier.

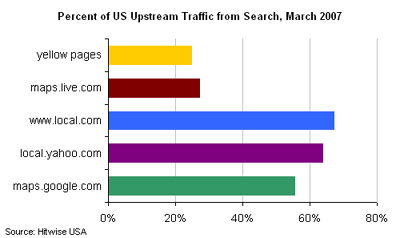

So what separates Geosign from the rest of the local universe, which also depends heavily on search-engine traffic? Witness this chart from Hitwise, recently highlighted by Mike Boland at Kelsey:

It’s arguable that Geosign is just the chart’s reductio ad absurdum. Obviously we can make distinctions, but I’d be worried if I were above, say, 35% on this chart and I weren’t Google or Yahoo.

OK, it’s definitely impressive that Local.com gets more of its traffic from search engines than does either Yahoo Local or Google Maps. Probably the same is true of Marchex, which operates domains like 20176.com.

But if Google and Yahoo want to move their own bars to the right, they can easily do so. It’ll come from the hide of Local.com, Marchex and similar companies.

And one big lesson of Geosign, scary and refreshing both, is that Google is willing to nuke a 9-digit business overnight.

by Laurence | Sep 19, 2007 | Local search

Yellow Pages folks surely do love structure — especially when it comes to data. Here at the latest Kelsey conference, where YP folks abound, the only good datum is a structured datum.

Consider the title of yesterday’s most interesting panel:

Building a Better Database: Acquiring Content in a Dysfunctional Environment

The title is a bit grad school, but “dysfunctional” is a strong word that caught my eye. Here it mostly means “resistant to structure.”

And them’s fightin’ words in the world of Yellow Pages.

By now I’ve gone to a bunch of YP-oriented conferences. All of them featured a discussion about how to gather structured data. But I’m starting to suspect that this isn’t the most important problem to solve — and not just because these conference discussions never go anywhere.

Here’s my thinking:

In what a YPer would call a functional environment, every business location, small or large, would authorize a regularly updated master version of its “attributes” (hours, certifications, parking facilities, etc.), and would post this information in some microformat on its Web site, or supply it directly to each data vendor, or send it to an industry-wide data clearinghouse that’ll probably never exist.

In addition, lots of other data sources — licensing bodies, rating sites, whatever — would distribute structured information that’s already normalized and can be correlated perfectly to these master records.

All this data would then be collated by data vendors such as Localeze and sold to Web companies such as Google or, for that matter, Loladex.

Finally, the Web companies would build applications that use the structured data for searching by consumers (input) and display to consumers (output).

This worldview may be summarized thus:

More structured data in → Better answers out.

Or as Marchex‘s Matthew Berk (who’s a smart guy) said at the panel here: “We think local search is about structured search.”

Berk gave a very good example, which I also use when discussing Loladex: If you’re looking for a doctor, you need to know whether he takes your insurance. That’s true, without a doubt.

But here’s the problem I have:

The majority of information available about any company, and particularly about any small company, will never be structured. It’ll exist only on the general Web, where it must be searched on its own terms — that is, as unstructured text.

To me, this suggests that the most pressing data problem isn’t how to gather more structured data, but how to search unstructured data (on Web pages) and return structured answers.

I live on both sides of this equation, by the way. My wife runs a small cookie bakery, and I’m in charge of distributing her data to online sources.

Because of my background, I’m more informed and motivated than most small business owners. And yet, to be honest, just keeping her Web site up-to-date is a chore. On Yelp right now, I’m sorry to say, her hours are incorrect. I should update it, but I just haven’t.

Accuracy on our own Web site is always my #1 priority, because that’s our official voice. Also it’s where most people land when they search for “Lola Cookies.”

Keeping Yahoo Local accurate is on my list, too, but it’s lower down. Ditto Google and YellowPages.com and the other big sites.

I never think about the data vendors one layer back, like InfoUSA, unless they happen to call the store. (Which InfoUSA does, to its credit.)

Meanwhile, plenty of interesting and searchable information about the bakery exists in other places on the Web, in formats that aren’t even addressed by the concept of “attributes.”

A TV broadcast from the bakery aired live on the local morning news recently, for instance. If you watched the show, you might search for us with a term like “fox 5 cookies virginia.” Where does that fit in the world of structured data?

I raised this general issue at yesterday’s panel. What were the panelists doing about this wealth of unstructured Web data, which right now is the dark matter of the local-search universe?

The answer I got was, basically, “Not much.”

Most panelists said they do only highly targeted crawls, focusing on sites that have structured data that can “extend or validate” their own data, in the words of Localeze’s Jeff Beard. An example might be the site of a professional group such as the American Optometric Association.

No panelist was ready to start indexing the sites of individual businesses, or locally focused blogs, or any other sites that are unstructured but potentially rich in content.

The only (mild) exception was Erron Silverstein of YellowBot, who also said his company limits itself to targeted crawls — but included local media, such as newspapers, among his targets.

A few players are indexing the broader Web and then associating pages with specific businesses (which is the important part). Most notable are Google and Yahoo, who do it for their local search products.

Of course, they’re already indexing the entire Web. It’s less of a stretch for them.

Google and Yahoo also buy structured data from InfoUSA, Localeze and others, so it’s not like such data is obsolete. But they’re getting the same info directly from some businesses, and those updates are likely more timely, more accurate, and more complete.

Meanwhile, their Web indices are opening up a realm of data that traditional vendors like Acxiom — represented by Jon Cohn on yesterday’s panel — simply don’t care to address.

I suspect that, sooner than you’d imagine, Google and Yahoo will be buying structured data not so that users can search it directly, but for two less-flattering reasons:

- To help find Web pages they can associate with each business

- To fill ever-smaller gaps in the coverage that results from #1

Matthew Berk of Marchex argued that a good local search must be structured to “help someone walk down the decision trail” by using filters to narrow their search progressively:

I need a orthopedist in Boston … in the Back Bay … who accepts United Healthcare.

I think users are more likely to learn that they can go to Google and type “orthopedist back bay united healthcare” — particularly if it produces a good top result the first time they try.

The burden of local search, it seems to me, is to do something that Google can’t match with an unstructured Web search.

In any case, the search portals will ultimately use their indexed Web pages to extract and cross-check structured data directly. Over time — probably just a couple of years — such automated processes will yield data that’s more current and detailed than anything that’s produced by scanning phone books or calling stores.

The resulting search functionality, integrating both structured and unstructured data, will be sold to other companies as a Web service, and data vendors such as InfoUSA will become irrelevant to local search.

Now that would be a dysfunctional environment for many of the Kelsey attendees.

I’m not sure exactly how companies like InfoUSA and Acxiom should tackle the unstructured Web. It’ll demand a new way of thinking, and probably a new way of selling.

But I’m certain that they ignore unstructured data at their peril.